Take a photo of a barcode or cover

I thought I'd like the book but...

It was not what I expected. It was dense. The topics covered didn't interest me or, more like, I didn't find the way they were written interesting (or the chosen information). I haven't actually read all the chapters. Plus, I skim read some of them. The library/private collectors chapter was the most interesting one, I think.

It was not what I expected. It was dense. The topics covered didn't interest me or, more like, I didn't find the way they were written interesting (or the chosen information). I haven't actually read all the chapters. Plus, I skim read some of them. The library/private collectors chapter was the most interesting one, I think.

A book about books, what’s not to like?!

Really enjoyed this dive into the world of books, books shops and the history of books/libraries

Really enjoyed this dive into the world of books, books shops and the history of books/libraries

Excellent smorgasbord of interesting facts and tales.

informative

lighthearted

relaxing

medium-paced

This is a delightful treasure trove, which makes you appreciate the book even more. Sometimes it suffers under the weight of its own pretensions, which is where the prose can drag a little. Most of the time, though, a fascinating, diverting and life-affirming love affair with the book.

Minor: Death, Torture

I enjoyed this book as it was a great diversion. At times the name dropping and giant words became tiresome but overall enjoyable!

informative

inspiring

reflective

slow-paced

An enjoyable history of literacy and the book trade. There's a bit of memoir in here too but it's not the focus. Pairs well with Alberto Manguel's books on reading.

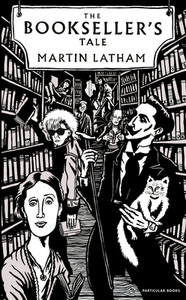

The blurb describes this book as "part cultural history, part literary love letter and part reluctant memoir".

The first part of the sentence seems to make up the bulk of the content - there is a lot of cultural history included in the book; I particularly liked the sections on libraries throughout history, street booksellers and the bookstore customers. The book contains a collection of anecdotes from the history of books that allowed me to see a different side to bibliography. At one point it was mentioned that this book was a 10-year project; I can well believe it, the subject matter throughout (all parts of it) are very clearly researched.

The literary love letter part felt a little lacking for me; while it is clear that the author has a lot of passion for books and has dedicated a large portion of his life to bibliography, the writing felt a cold at times. There were moments of humour (I found myself chuckling at certain one-liners or fun facts that were included) but at times I found myself feeling like I was reading a textbook. It was a decent read, but there were parts dotted throughout where I struggled to stay engaged.

On to the part reluctant memoir - reluctant is certainly the right word. I don't feel like I got to know much of anything substantial about the author until the very end of the book (the last 30 pages or so). This is a man who appears to have a fascinating personal story that is woven into the bookstore that he has headed for so many years (and the ones he worked at before), I would have loved to have seen more of it. The book had room for an increased feeling of personality and space for more stories from 30 years of running a well-known bookstore - I think I would have connected with it more if they had been a bigger feature.

I've come away from this read knowing a lot more about the world of bibliography than I did before, but it didn't leave the lasting impression on me that I hoped it would.

The first part of the sentence seems to make up the bulk of the content - there is a lot of cultural history included in the book; I particularly liked the sections on libraries throughout history, street booksellers and the bookstore customers. The book contains a collection of anecdotes from the history of books that allowed me to see a different side to bibliography. At one point it was mentioned that this book was a 10-year project; I can well believe it, the subject matter throughout (all parts of it) are very clearly researched.

The literary love letter part felt a little lacking for me; while it is clear that the author has a lot of passion for books and has dedicated a large portion of his life to bibliography, the writing felt a cold at times. There were moments of humour (I found myself chuckling at certain one-liners or fun facts that were included) but at times I found myself feeling like I was reading a textbook. It was a decent read, but there were parts dotted throughout where I struggled to stay engaged.

On to the part reluctant memoir - reluctant is certainly the right word. I don't feel like I got to know much of anything substantial about the author until the very end of the book (the last 30 pages or so). This is a man who appears to have a fascinating personal story that is woven into the bookstore that he has headed for so many years (and the ones he worked at before), I would have loved to have seen more of it. The book had room for an increased feeling of personality and space for more stories from 30 years of running a well-known bookstore - I think I would have connected with it more if they had been a bigger feature.

I've come away from this read knowing a lot more about the world of bibliography than I did before, but it didn't leave the lasting impression on me that I hoped it would.

3.5 stars. Solid collection of anecdotes about how we treat books: collecting, selling, taking notes in the margins. Some of them are quite humorous (my favorite is about the new British Library), some drier, but Latham writes engagingly throughout. This would be a good book to keep on the bedside table.

Contrary to what the title suggests, The Bookseller's Tale isn't a tale about the life of a bookseller (unlike, say, The Diary of a Bookseller). Think of it more as a love letter, a series of musings on books and reading, curated snippets on the history of books. If you're looking for a punchy read, this probably isn't it. But if you're up for a meandering ramble punctuated by the odd fascinating factoid, this book could be up your alley.

The first few chapters of The Bookseller's Tale, for me, offered prompts for reflection on our reading habits, on the hard fought privilege to read and how our reading context and relationship with books has evolved over the years. For instance, the opening chapter on Comfort Books - that category of books that Latham describes as those having "the ability to take us away to a better place….a strange mishmash of 'trash' and 'classics'" - led to a good amount of musing and reflection on my part on what my own comfort books were. (For the record: Austen, Harry Potter, Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle are up there for me). Latham observes from his own experience selling books that this category would include such titles as Cloud Atlas, Against Nature, Watchman, I Capture the Castle, The Catcher in the Rye, Tristam Shandy, The Earthsea Trilogy, LOTR, Anne of Green Gables, the Harry Potter books, the Phantom Tollbooth, The Little Prince, The Alchemist, the Jeeves books and Cold Comfort Farm. He notes how we have very different relationships with various books - "the books with an element of duty in the reading, and books you get up earlier in the morning for, and slow down near the end to delay parting from."

Chapter 2 (Reading in Adversity) was fascinating in describing how determined and passionate the working class were about reading - London cobbler James Lackington and his colleagues would take turns to read to each other as they worked; two footmen in St James Palace in the reign of Queen Anne made a fortune selling palace candle ends at a market stall after work to feed the working class's desire to read after dark (their names were Fortnum and Mason); stories of shepherds amassing mini personal libraries; coal miners establishing miners' libraries and one Nottinghamshire miner being clouted by his foreman for making a mistake while reading poetry only to have that same foreman subsquently recommend he read Shelley instead. Latham makes us realise that working class reading isn't necessarily rare, just "under-represented in biographies and in histories of the book" and that even "when proletarian reading is analysed, it is still sometimes done with condescension".

Chapter 5 on libraries offers not only a brief history of libraries - from ancient libraries where the world's wisdom was collected to how historical notions of the library differed significantly from our modern conception of the library as a place for silent reading and contemplation. Latham notes for instance that "many ancient Greek and Roman libraries were housed in public baths, which were general relaxation centres." Meanwhile, book historian Andrew Pettegree described the Renaissance library as "a noisy place - a place for conversation and display, rather than for study and contemplation…[it was only in the seventeenth century that the library began]…its long descent into silence, emerging as that new phenomenon of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the library as mausoleum, the silent repository of countless unread books."

We learn about the fight to democratise libraries, to make them accessible to all, rather than limiting them to elite scholars. But it was this line in particular that stuck with me, that captured what is so magical about the library experience: "browsing a library is to browsing online (jerked around by algorithms) what free climbing is to a coach tour".

Chapter 8 on Signs of Use made me reflect on my own notions of what a book should be like and what shaped these attitudes. Should a book be treated with reverence - kept pristine with no creases and dog ears - or should we think of a book as having character when it's marked up with marginalia? Up until the 1960s, marginalia were thought to sully books and libraries would ignore or bleach off marginalia. Latham notes that with mass production making new things more widely available, "secondhand things became a mark of lower status. To be rich and modern was to possess new stuff [and] a craze for pristine books became almost provenance-phobia, a sort of War on Terroir." Today, many are still ambivalent about marginalia while others see marginalia as a means of gaining additional insights into famous people's thinking (think Newton, Luther, Coleridge and Blake), or perhaps a glimpse into every day life in a different age.

If you love factoids, The Bookseller's Tale is a treasure trove of them. In Chapter 3, on The Strange Emotional Power of Cheap Books - we learn about the phenomenon of the "chapbook", short cheap books from 1550 to the late 19th century whose pages were typically recycled as pie-paper or worse (i.e. toilet paper). Think "tales of ghosts, crimes, knightly quests, sleeping princesses, star-crossed lovers and misdemeanours, miracles and wonders" - guilty pleasures. Some were also abridged versions of "great" novels.

Or Chapter 4 on Book Pedlars, where we learn about the great book markets in both the UK and beyond (e.g. such cities as Yangon, Cairo, Istanbul, Baghdad and various Indian cities including Kolkata). It was fascinating to learn how, in London, book pedlars clustered in places like Old Bailey, Bedlam (because the lunatics housed there were considered a visitor attraction and hence had a lot of footfall) and later Farringdon Road.

In Chapter 6 (Private Passions: Collectors), we learn not only about passionate and eccentric collectors and bibliophiles, but also about incunabula - "books produced in the infancy of printing, before 1500" - and incunabulists, those who collect or are interested in incunabula. We also learn about "fore-edge paintings" - pictures painted on the very edges (not the margins) of a book in such a way that they are only visible when the pages are bent or 'fanned'.

Meanwhile, Chapter 7 was a fascinating foray into the world of Medieval Marginalia - how medieval books might not only have illustrations in the margins of flora and fauna, but also comic scenes (like animals farting at each other next to the text on Jesus's temptation in the desert), profane scenes (a nun suckling a monkey, a naked couple copulating on a prayer book page, a woman riding an "eight foot disembodied cock around like a jet ski").

And who knew that in the UK, Boots the Chemist used to run pay-to-borrow lending libraries, lending some 35 million books a year in 1938?? Its customers were traditionally the poorest of society and their libraries helped the cause of popular education. Boots libraries only closed down in 1966, when the Public Libraries Act required all councils to provide free libraries.

Or that in the British Library, four double height sub-basements extend 75 feet below the ground where most of the books are stored in "chilled conditions, except for the rarest items, which are in oxygen-free rooms filled with a synthetic argon-based gas called Inergen, a mixture which cannot catch fire." And in the event that a fire starts in the non-rare books areas, a water sprinkler system is activated, followed by a Blast Free Wind Tunnel to dry the books without heating them. Staff train on wet telephone directories to operate the system. The Library also has audio studios built on a giant two-foot thick rubber pad to eliminate noise in order to transcribe their cassette recordings of authors before they degrade. Mind boggling.

What I loved most of all about this meandering ramble that is The Bookseller's Tale is that it made me want explore more, to wander further afield, both literally and figuratively. Reading this book, I wanted to visit the Laurentian Library in Florence designed by Michaelangelo and commissioned by his childhood friend Pope Clement; the Buddhist Library in Nara, Japan; Toyo Ito's Sendai Mediatheque and Tama Art University Library. I wanted to visit the Mafra Library in Portugal, which has a gallery projecting into the room, from which hundreds of tiny inch-long bats emerge from their roosting places each night to eat insects that might threaten the books! (The staff have to cover the furniture each evening to catch the bats' droppings). And of course visits to bookshops. Not just familiar ones like Shakespeare and Co in Paris or the Strand in NY, but new ones I learned about after reading this book, like The Monkey's Paw in Toronto and Montague Bookmill Bookshop in Massachusetts. And it was difficult sometimes to read without stopping to make a note of yet another new book to check out - a book on Latham's list of comfort books that I hadn't read, books and authors customers were hunting down, books customers would buy multiple copies of to give away, books they would re-read.

The first few chapters of The Bookseller's Tale, for me, offered prompts for reflection on our reading habits, on the hard fought privilege to read and how our reading context and relationship with books has evolved over the years. For instance, the opening chapter on Comfort Books - that category of books that Latham describes as those having "the ability to take us away to a better place….a strange mishmash of 'trash' and 'classics'" - led to a good amount of musing and reflection on my part on what my own comfort books were. (For the record: Austen, Harry Potter, Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle are up there for me). Latham observes from his own experience selling books that this category would include such titles as Cloud Atlas, Against Nature, Watchman, I Capture the Castle, The Catcher in the Rye, Tristam Shandy, The Earthsea Trilogy, LOTR, Anne of Green Gables, the Harry Potter books, the Phantom Tollbooth, The Little Prince, The Alchemist, the Jeeves books and Cold Comfort Farm. He notes how we have very different relationships with various books - "the books with an element of duty in the reading, and books you get up earlier in the morning for, and slow down near the end to delay parting from."

Chapter 2 (Reading in Adversity) was fascinating in describing how determined and passionate the working class were about reading - London cobbler James Lackington and his colleagues would take turns to read to each other as they worked; two footmen in St James Palace in the reign of Queen Anne made a fortune selling palace candle ends at a market stall after work to feed the working class's desire to read after dark (their names were Fortnum and Mason); stories of shepherds amassing mini personal libraries; coal miners establishing miners' libraries and one Nottinghamshire miner being clouted by his foreman for making a mistake while reading poetry only to have that same foreman subsquently recommend he read Shelley instead. Latham makes us realise that working class reading isn't necessarily rare, just "under-represented in biographies and in histories of the book" and that even "when proletarian reading is analysed, it is still sometimes done with condescension".

Chapter 5 on libraries offers not only a brief history of libraries - from ancient libraries where the world's wisdom was collected to how historical notions of the library differed significantly from our modern conception of the library as a place for silent reading and contemplation. Latham notes for instance that "many ancient Greek and Roman libraries were housed in public baths, which were general relaxation centres." Meanwhile, book historian Andrew Pettegree described the Renaissance library as "a noisy place - a place for conversation and display, rather than for study and contemplation…[it was only in the seventeenth century that the library began]…its long descent into silence, emerging as that new phenomenon of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the library as mausoleum, the silent repository of countless unread books."

We learn about the fight to democratise libraries, to make them accessible to all, rather than limiting them to elite scholars. But it was this line in particular that stuck with me, that captured what is so magical about the library experience: "browsing a library is to browsing online (jerked around by algorithms) what free climbing is to a coach tour".

Chapter 8 on Signs of Use made me reflect on my own notions of what a book should be like and what shaped these attitudes. Should a book be treated with reverence - kept pristine with no creases and dog ears - or should we think of a book as having character when it's marked up with marginalia? Up until the 1960s, marginalia were thought to sully books and libraries would ignore or bleach off marginalia. Latham notes that with mass production making new things more widely available, "secondhand things became a mark of lower status. To be rich and modern was to possess new stuff [and] a craze for pristine books became almost provenance-phobia, a sort of War on Terroir." Today, many are still ambivalent about marginalia while others see marginalia as a means of gaining additional insights into famous people's thinking (think Newton, Luther, Coleridge and Blake), or perhaps a glimpse into every day life in a different age.

If you love factoids, The Bookseller's Tale is a treasure trove of them. In Chapter 3, on The Strange Emotional Power of Cheap Books - we learn about the phenomenon of the "chapbook", short cheap books from 1550 to the late 19th century whose pages were typically recycled as pie-paper or worse (i.e. toilet paper). Think "tales of ghosts, crimes, knightly quests, sleeping princesses, star-crossed lovers and misdemeanours, miracles and wonders" - guilty pleasures. Some were also abridged versions of "great" novels.

Or Chapter 4 on Book Pedlars, where we learn about the great book markets in both the UK and beyond (e.g. such cities as Yangon, Cairo, Istanbul, Baghdad and various Indian cities including Kolkata). It was fascinating to learn how, in London, book pedlars clustered in places like Old Bailey, Bedlam (because the lunatics housed there were considered a visitor attraction and hence had a lot of footfall) and later Farringdon Road.

In Chapter 6 (Private Passions: Collectors), we learn not only about passionate and eccentric collectors and bibliophiles, but also about incunabula - "books produced in the infancy of printing, before 1500" - and incunabulists, those who collect or are interested in incunabula. We also learn about "fore-edge paintings" - pictures painted on the very edges (not the margins) of a book in such a way that they are only visible when the pages are bent or 'fanned'.

Meanwhile, Chapter 7 was a fascinating foray into the world of Medieval Marginalia - how medieval books might not only have illustrations in the margins of flora and fauna, but also comic scenes (like animals farting at each other next to the text on Jesus's temptation in the desert), profane scenes (a nun suckling a monkey, a naked couple copulating on a prayer book page, a woman riding an "eight foot disembodied cock around like a jet ski").

And who knew that in the UK, Boots the Chemist used to run pay-to-borrow lending libraries, lending some 35 million books a year in 1938?? Its customers were traditionally the poorest of society and their libraries helped the cause of popular education. Boots libraries only closed down in 1966, when the Public Libraries Act required all councils to provide free libraries.

Or that in the British Library, four double height sub-basements extend 75 feet below the ground where most of the books are stored in "chilled conditions, except for the rarest items, which are in oxygen-free rooms filled with a synthetic argon-based gas called Inergen, a mixture which cannot catch fire." And in the event that a fire starts in the non-rare books areas, a water sprinkler system is activated, followed by a Blast Free Wind Tunnel to dry the books without heating them. Staff train on wet telephone directories to operate the system. The Library also has audio studios built on a giant two-foot thick rubber pad to eliminate noise in order to transcribe their cassette recordings of authors before they degrade. Mind boggling.

What I loved most of all about this meandering ramble that is The Bookseller's Tale is that it made me want explore more, to wander further afield, both literally and figuratively. Reading this book, I wanted to visit the Laurentian Library in Florence designed by Michaelangelo and commissioned by his childhood friend Pope Clement; the Buddhist Library in Nara, Japan; Toyo Ito's Sendai Mediatheque and Tama Art University Library. I wanted to visit the Mafra Library in Portugal, which has a gallery projecting into the room, from which hundreds of tiny inch-long bats emerge from their roosting places each night to eat insects that might threaten the books! (The staff have to cover the furniture each evening to catch the bats' droppings). And of course visits to bookshops. Not just familiar ones like Shakespeare and Co in Paris or the Strand in NY, but new ones I learned about after reading this book, like The Monkey's Paw in Toronto and Montague Bookmill Bookshop in Massachusetts. And it was difficult sometimes to read without stopping to make a note of yet another new book to check out - a book on Latham's list of comfort books that I hadn't read, books and authors customers were hunting down, books customers would buy multiple copies of to give away, books they would re-read.