You need to sign in or sign up before continuing.

Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Reading this book wasn't exactly a pleasure. I really like how Jean Rhys writes, her simple but magical language and images she uses. But the stories and people she writes about, that's a completely different story.

With my life experiences and my nature I simply can't enjoy her utterly pesimistic view on life. I undrestand, that her charecters (or better said - Rhys herself) went through many hardships, such hardships that I cannot even imagine. But still, there's no spark of hope. Not a little one.

It seems that Julia and her lovers live their lives without a smallest spark of passion for anything. They're completely frustrated and they do nothing to make their situations better, more bearable or pleasant. The question of money seems to set Julia apart from all the men in her life, but would she be happier being wealthy? I don't think so.

So, all in all, I think this is a very well written book. But it is not enjoyable for everyone.

With my life experiences and my nature I simply can't enjoy her utterly pesimistic view on life. I undrestand, that her charecters (or better said - Rhys herself) went through many hardships, such hardships that I cannot even imagine. But still, there's no spark of hope. Not a little one.

It seems that Julia and her lovers live their lives without a smallest spark of passion for anything. They're completely frustrated and they do nothing to make their situations better, more bearable or pleasant. The question of money seems to set Julia apart from all the men in her life, but would she be happier being wealthy? I don't think so.

So, all in all, I think this is a very well written book. But it is not enjoyable for everyone.

emotional

reflective

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

emotional

reflective

fast-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Character

Strong character development:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

3.25 ish maybe 3.5 - this book is reminiscent of books like The Awakening that explore sad women in a time when their worth is primarily tied to a man’s interest. Other books have provided more depth in the story than this one, hence my rating.

“After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie” follows Julia in the wake of leaving Mr. Mackenzie. She was once married, and after leaving her husband proceeds to live off of her youth and beauty through well-off men who put her up.

Julia is depressed, lonely, and severely lacks a shred of self-confidence in her rising age (of 36, lol). Her happiness is heavily reliant on what her value is in others eyes, which is diminishing in her age. She visits her family which truly brings out the worst in her (as most do). She ruminates over her thoughts and her life with a gray and tired lens.

I read this in a day. If you’re a sad girl and like reading that sort of thing, I would recommend this book. There’s a good amount of insight into depressive thoughts and familial and romantic relationships, especially with those who struggle and are readily reliant on others.

Don’t read this if you are seeking character development or any significant plot. Julia is herself from start to finish.

It’s hard to complain about a quick read like this one, as I’ve always said.

Some highlights:

“And then I was frightened, and yet I know that if I could get to the end of what I was feeling it would be the truth about myself and about the world and about everything that one puzzled and pains about all the time.”

“It was the darkness that got you. It was heavy darkness, greasy and compelling. It made walls around you, and shut you in so that you felt you could not breathe. You wanted to beat at the darkness and shriek and be let out. And after a whip you got used to it. Of course. And then you stopped believing that there was anything else anywhere.”

“Every day is a new day; every day you are a new person. What have you to do with the day before?”

“The last time you were happy about nothing; the first time you were afraid about nothing. Which came first?”

“After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie” follows Julia in the wake of leaving Mr. Mackenzie. She was once married, and after leaving her husband proceeds to live off of her youth and beauty through well-off men who put her up.

Julia is depressed, lonely, and severely lacks a shred of self-confidence in her rising age (of 36, lol). Her happiness is heavily reliant on what her value is in others eyes, which is diminishing in her age. She visits her family which truly brings out the worst in her (as most do). She ruminates over her thoughts and her life with a gray and tired lens.

I read this in a day. If you’re a sad girl and like reading that sort of thing, I would recommend this book. There’s a good amount of insight into depressive thoughts and familial and romantic relationships, especially with those who struggle and are readily reliant on others.

Don’t read this if you are seeking character development or any significant plot. Julia is herself from start to finish.

It’s hard to complain about a quick read like this one, as I’ve always said.

Some highlights:

“And then I was frightened, and yet I know that if I could get to the end of what I was feeling it would be the truth about myself and about the world and about everything that one puzzled and pains about all the time.”

“It was the darkness that got you. It was heavy darkness, greasy and compelling. It made walls around you, and shut you in so that you felt you could not breathe. You wanted to beat at the darkness and shriek and be let out. And after a whip you got used to it. Of course. And then you stopped believing that there was anything else anywhere.”

“Every day is a new day; every day you are a new person. What have you to do with the day before?”

“The last time you were happy about nothing; the first time you were afraid about nothing. Which came first?”

Julia, a woman is down on her lick, losing her looks and body and the affair with the man who was supporting her is over. She has no friends and very little family. She is desultory, depressed, and unmoored as she travels from Paris to London, where her mother is dying. She is in crisis and sinking fast.

Every one of Jean Rhys's early novels is about what it's like for a woman who can't earn money, or the sympathy of a man who could give her some. This one, though, is the apex of this theme. Julia lives in a misery of other people's generosity, skidding from one situation to another with the mad and irrational mental budgeting and bargaining of the truly broke, and apparently no way of earning her own fee for a hotel room for a few weeks.

When the novel starts, she's been coasting on a depressive plateau, hiding in a room without going out for months, while the last man to have dropped her (Mr Mackenzie, of course) has been paying a pity allowance. Once this is cut off, she is sort of passively set in motion like a living law of physics, and slowly ricochets around, looking for options and slowly crumbling from anxiety and lost hope. Trying to k-i-t keep-it-together. "As if at this time of day she did not know that when you were in trouble the only possible thing to do was to hide it as long as you could."

I did really feel for Julia, and much like this author's other books, I really liked reading it except for the fact that the ending is so unrelentingly bleak that it nearly sours the thing. Julia, though, has a fuller backstory to vouch for her troubles, and then the plot thrusts her back into her own history as well. It's tragic and psychological and very moving. I can recommend the book on that strength, but with the caveat that one does need to keep one's own spirits up. (Speaking of, until I started reading Jean Rhys's Parisian novels, I'd never heard of Pernod in my life, and now I feel like I've drunk a thousand.)

I liked this book a lot, but now having finished both, it feels as though the author was gearing up here to write Good Morning, Midnight, which accomplishes a lot of this over again but with a far heavier sting. These women are so like each other, of similar ages in such similar situations (although, one resides in Paris and spends a fraught holiday in London, and in the next the situation is reversed).

What makes this book special is that period Julia spends with her relatives back in England, looking for some kind of help and instead finding more and deeper loss. This resonates so much more heavily than any of the Paris goings-on, it almost makes the rest of the book feel insignificant. Her sister, especially, enters into view as a rival for our sympathy and understanding. But it, too, is harsh. In the world this author built, there's not really a good, safe example for a woman to be.

When the novel starts, she's been coasting on a depressive plateau, hiding in a room without going out for months, while the last man to have dropped her (Mr Mackenzie, of course) has been paying a pity allowance. Once this is cut off, she is sort of passively set in motion like a living law of physics, and slowly ricochets around, looking for options and slowly crumbling from anxiety and lost hope. Trying to k-i-t keep-it-together. "As if at this time of day she did not know that when you were in trouble the only possible thing to do was to hide it as long as you could."

I did really feel for Julia, and much like this author's other books, I really liked reading it except for the fact that the ending is so unrelentingly bleak that it nearly sours the thing. Julia, though, has a fuller backstory to vouch for her troubles, and then the plot thrusts her back into her own history as well. It's tragic and psychological and very moving. I can recommend the book on that strength, but with the caveat that one does need to keep one's own spirits up. (Speaking of, until I started reading Jean Rhys's Parisian novels, I'd never heard of Pernod in my life, and now I feel like I've drunk a thousand.)

I liked this book a lot, but now having finished both, it feels as though the author was gearing up here to write Good Morning, Midnight, which accomplishes a lot of this over again but with a far heavier sting. These women are so like each other, of similar ages in such similar situations (although, one resides in Paris and spends a fraught holiday in London, and in the next the situation is reversed).

What makes this book special is that period Julia spends with her relatives back in England, looking for some kind of help and instead finding more and deeper loss. This resonates so much more heavily than any of the Paris goings-on, it almost makes the rest of the book feel insignificant. Her sister, especially, enters into view as a rival for our sympathy and understanding. But it, too, is harsh. In the world this author built, there's not really a good, safe example for a woman to be.

challenging

dark

emotional

reflective

sad

slow-paced

Plot or Character Driven:

Plot

Strong character development:

No

Loveable characters:

No

Diverse cast of characters:

No

Flaws of characters a main focus:

Yes

I loved this just as much as Good Morning, Midnight. Julia wanders around Paris, London, and Paris again moving from cheap hotel to boardinghouse living off the money she can get from men. Middle class and middle-aged she has no prospects of marriage and no likelihood of employment. It's sad and depressing but has Rhys's wonderful clean, unsentimental writing.

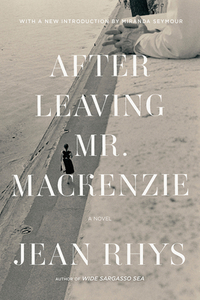

Jean Rhys was the pen name of Ella Williams. Born in the Caribbean island of Dominica, Rhys lived most of her adult life in England. Rhys published several books, beginning with The Left Bank, a collection of short stories, in 1927. That was followed by a series of short novels over the next dozen years. Postures, later republished as Quartet, was published in 1928. (I reviewed Quartet here.) After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, Rhys’ second novel, came out in 1930, and was followed by Voyage in the Dark in 1934, and Good Morning, Midnight in 1939. Although these books are now regarded as classics of modernism, at the time they didn’t exactly set the world on fire. After Good Morning, Midnight, Rhys disappeared from sight, enough so that a BBC producer who was producing a radio version of Good Morning, Midnight in the mid-1950’s actually took out ads in newspapers, asking about Rhys’ whereabouts. It turned out that Rhys was still alive. She published just two more books during her lifetime, the critically acclaimed Wide Sargasso Sea in 1966, which finally brought her out of obscurity, and Sleep it Off Lady, a collection of short stories which appeared in 1976. Rhys died in 1979 at the age of either 88 or 84. (The Penguin edition of After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie gives her birth year as 1894, Wikipedia says 1890.)

Rhys’ novels from the 1920’s and 1930’s generally deal with the lives of women who are dependent on men for their financial security. I’ve read Quartet, After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, and Good Morning, Midnight, and they all fit together very well. Rhys’ lead female characters don’t have enough education to find a profession, so they end up drifting from man to man, eking out an existence thanks to the generosity of their male companions. Rhys had a very interesting comment in her interview with The Paris Review in 1979, the year she died:

“When I was excited about life, I didn’t want to write at all. I’ve never written when I was happy. I didn’t want to. But I’ve never had a long period of being happy. Do you think anyone has? I think you can be peaceful for a long time. When I think about it, if I had to choose, I’d rather be happy than write. You see, there’s very little invention in my books. What came first with most of them was the wish to get rid of this awful sadness that weighed me down.” Jean Rhys, The Paris Review interview, 1979.

After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie tells the story of Julia Martin, who has, well, left Mr. Mackenzie as the novel opens. We follow Julia as the checks from Mr. Mackenzie suddenly stop arriving, and she returns to London after ten years in Paris. In London, Julia reckons with her sister Norah, who has been caring for their invalid mother, now at death’s door.

I don’t want to give too much away by adding more plot summary, and anyway, After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie is not a novel that depends much on its plot. Of note to literary fans: in the novel there is a quote from Almayer’s Folly, Joseph Conrad’s first novel, published in 1895, which indicates that Conrad’s work must have been an influence on Rhys. Like Conrad, who was Polish by birth, Rhys no doubt felt herself an outsider to British culture.

There are many excellent quotes in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie that demonstrate Jean Rhys’ keen observance of human nature. Some of my favorites are:

“Her mind was a confusion of memory and imagination.” (p.9)

“Once you started letting the instinct of pity degenerate from the general to the particular, life became completely impossible.” (p.34)

“It was as if I were before a judge, and I were explaining that everything I had done had always been the only possible thing to do. And of course I forgot that it’s always so with everybody, isn’t it?” (p.40)

“Perhaps the last ten years had been a dream; perhaps life, moving on for the rest of the world, had miraculously stood still for her.” (p.48)

If you’re interested in modernism, or in great writing, you need to read Jean Rhys.

Rhys’ novels from the 1920’s and 1930’s generally deal with the lives of women who are dependent on men for their financial security. I’ve read Quartet, After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, and Good Morning, Midnight, and they all fit together very well. Rhys’ lead female characters don’t have enough education to find a profession, so they end up drifting from man to man, eking out an existence thanks to the generosity of their male companions. Rhys had a very interesting comment in her interview with The Paris Review in 1979, the year she died:

“When I was excited about life, I didn’t want to write at all. I’ve never written when I was happy. I didn’t want to. But I’ve never had a long period of being happy. Do you think anyone has? I think you can be peaceful for a long time. When I think about it, if I had to choose, I’d rather be happy than write. You see, there’s very little invention in my books. What came first with most of them was the wish to get rid of this awful sadness that weighed me down.” Jean Rhys, The Paris Review interview, 1979.

After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie tells the story of Julia Martin, who has, well, left Mr. Mackenzie as the novel opens. We follow Julia as the checks from Mr. Mackenzie suddenly stop arriving, and she returns to London after ten years in Paris. In London, Julia reckons with her sister Norah, who has been caring for their invalid mother, now at death’s door.

I don’t want to give too much away by adding more plot summary, and anyway, After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie is not a novel that depends much on its plot. Of note to literary fans: in the novel there is a quote from Almayer’s Folly, Joseph Conrad’s first novel, published in 1895, which indicates that Conrad’s work must have been an influence on Rhys. Like Conrad, who was Polish by birth, Rhys no doubt felt herself an outsider to British culture.

There are many excellent quotes in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie that demonstrate Jean Rhys’ keen observance of human nature. Some of my favorites are:

“Her mind was a confusion of memory and imagination.” (p.9)

“Once you started letting the instinct of pity degenerate from the general to the particular, life became completely impossible.” (p.34)

“It was as if I were before a judge, and I were explaining that everything I had done had always been the only possible thing to do. And of course I forgot that it’s always so with everybody, isn’t it?” (p.40)

“Perhaps the last ten years had been a dream; perhaps life, moving on for the rest of the world, had miraculously stood still for her.” (p.48)

If you’re interested in modernism, or in great writing, you need to read Jean Rhys.

Another devastating novel by Jean Rhys. (I'm reading/re-reading them in order of composition and this is her third.)

After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie one is a bit of a departure from her first two books, Voyage in the Dark and Quartet, insomuch as the text moves much more freely through the interior thoughts and impressions of the various characters and how they perceive and interpret each other. The narrative therefore creates less the tale of an alienated woman’s struggle against a hostile and abusive world (as seen in the other two novels) and more of a kind of panorama of souls crushed by their own indifference—each with a selfishness built of their own fears and disappointments. At first I found this panoramic shifting viewpoint less honest, somehow, that the first two novels and yearned for Julia’s perspective alone—to feel a purer empathy for her. As the novel progressed, however, I came to appreciate also seeing Julia from the outside, as the others interpreted her and her actions, and seeing how the other characters—Mr. Mackenzie, Horsefield, Uncle Griffiths, Mr. James, and Norah, Julia’s sister—each suffer their own interior alienation, and ultimately forgive themselves for their indifference and inability to feel or act upon their empathy for others. While, in the novel’s early scenes, these narrative driftings into other points of view seemed primarily to show how unfeeling the other characters were, as the narrative progresses, it actually fleshes out the other characters and deepened my view of Julia as well, neither saint nor total victim, but merely another semi-culpable soul traversing the wasteland of human selfishness known as society. While her sensitivity at first prompted my empathy more than the other, harder characters, of course it became, in the end, not much different than the selfish lack of understanding or inability to offer help of the various wealthy male characters.

As a species we have a lot of trouble believing that others suffer as we do and empathizing with that suffering rather than focusing on our own emotional and economic survival and feeling justified in preserving ourselves always with the excuse that things are hard, we’ve not had it easy, why should I go out of my way for you...etc. The biggest difference, of course, is that the male characters here have the economic means to help so their niggardliness makes them look more self-interested. In the end they are not—it’ s just that, as Julie says of Mr. James when he makes her feel bad for being needy, “It’s so easy to make a person who hasn’t got anything seem wrong.” Not that Julia deserves her fate—it’s just that aging, society, getting on...are all pitiless things.

After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie one is a bit of a departure from her first two books, Voyage in the Dark and Quartet, insomuch as the text moves much more freely through the interior thoughts and impressions of the various characters and how they perceive and interpret each other. The narrative therefore creates less the tale of an alienated woman’s struggle against a hostile and abusive world (as seen in the other two novels) and more of a kind of panorama of souls crushed by their own indifference—each with a selfishness built of their own fears and disappointments. At first I found this panoramic shifting viewpoint less honest, somehow, that the first two novels and yearned for Julia’s perspective alone—to feel a purer empathy for her. As the novel progressed, however, I came to appreciate also seeing Julia from the outside, as the others interpreted her and her actions, and seeing how the other characters—Mr. Mackenzie, Horsefield, Uncle Griffiths, Mr. James, and Norah, Julia’s sister—each suffer their own interior alienation, and ultimately forgive themselves for their indifference and inability to feel or act upon their empathy for others. While, in the novel’s early scenes, these narrative driftings into other points of view seemed primarily to show how unfeeling the other characters were, as the narrative progresses, it actually fleshes out the other characters and deepened my view of Julia as well, neither saint nor total victim, but merely another semi-culpable soul traversing the wasteland of human selfishness known as society. While her sensitivity at first prompted my empathy more than the other, harder characters, of course it became, in the end, not much different than the selfish lack of understanding or inability to offer help of the various wealthy male characters.

As a species we have a lot of trouble believing that others suffer as we do and empathizing with that suffering rather than focusing on our own emotional and economic survival and feeling justified in preserving ourselves always with the excuse that things are hard, we’ve not had it easy, why should I go out of my way for you...etc. The biggest difference, of course, is that the male characters here have the economic means to help so their niggardliness makes them look more self-interested. In the end they are not—it’ s just that, as Julie says of Mr. James when he makes her feel bad for being needy, “It’s so easy to make a person who hasn’t got anything seem wrong.” Not that Julia deserves her fate—it’s just that aging, society, getting on...are all pitiless things.

Skillfully written but entirely too elusive. Rhys writes with such venomous wit. Her message unsubtle but necessary. But the plot is unrefined and a chore to read, which is fitting to the theme but not my favorite take on the topic.