Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Some of these reviewers are slamming JCO, not for this memoir, but for being whiny, entitled, and melodramatic. Give the woman a break. She lost her husband of 47 years; she's allowed to be all these things, and more. Yes, it comes across heavy-handed at times, but Oates is writing about fresh and new pain with brutal honesty. I actually found the book comforting because it may have dwelled in darkness, but it didn't stay there forever.

I was supposed to hear JCO speak at UNLV when she suddenly had to cancel because of the death of her husband. That was years ago, so it was interesting for me to read this and get the backstory, of which I knew nothing. I'm still a huge fan of Oates' fiction, and I'm a huge fan of this.

I was supposed to hear JCO speak at UNLV when she suddenly had to cancel because of the death of her husband. That was years ago, so it was interesting for me to read this and get the backstory, of which I knew nothing. I'm still a huge fan of Oates' fiction, and I'm a huge fan of this.

A very interesting and compelling read about a woman's life the first year after her husband dies. It gave me some insight into the life my mother must have lead then, and beyond. I only wish Oates had children so I could understand how they fit into the grieving process. Often it was rambling and unorganized, but to criticize the widow for that would not only be harsh, but probably unrealistic.

I would have loved this book if the repetitive self-deprecating sections were cut. Also, the jarring 3rd person paragraphs and abundance of hyphens, exclamation points and parentheses became heavy-handed. But there was total identification with JCO's profound grieving, emptiness, incredible sadness and heart ache.

A grief memoir that is also a pleasure to read since Oates reveals a sense of humor, or her own sense of the absurd. She published this memoir only 3 years after her husband died, so the details are fresh. It's not until the 2nd to last paragraph that one discovers that she met a new husband 6 months after Ray Smith died, and practically the week she started to sleep normally again. There have been many critics of that: she clearly wrote this memoir while already with her new husband. But the memoir makes it very, very clear that Joyce Carol Oates, the writer, would not have existed without Raymond Smith, the husband. She needs a husband to survive. It is what it is.

This was still too raw for me to finish listening to. May go back to it someday, but need some escapism before delving into grief.

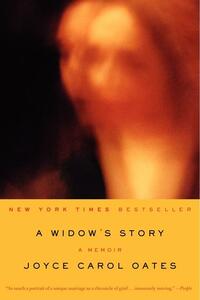

Written after the death of her husband of 46 years, Joyce Carol Oates' A Widow's Story: A Memoir (2011) and Sourland: Stories (2010) cover similar ground. A thesis could be written, and considering Oates' prominence in American letters may well be, about how she uses the two different forms — short stories and memoir — to synthesize experiences, observations, emotions and images and transform them into literature.

In A Widow's Story, the reader enters Oates' grieving — a harrowing, exhausting experience. When the reader puts the book aside — frequently — to take a break, to breathe it emphasizes the widow's plight — she has no ability to pause, no method of escape. Oates examines her personal grief intensely, but also comes to sees her state — one shared with other widows — as a kind of disease that must be lived through. Oates, who began writing her story as A Widow's Handbook, concludes that there is no profundity, no wisdom to be gained in grief, "...or, if there is...it's a wisdom one might do without." Instead, her advice boils down to a sentence, "...on the first anniversary of her husband's death the widow should think I kept myself alive."

Sourland: Stories contain many of the same ideas and images as Oates' memoir — hospitals as memory pools, the vulnerability of the surviving spouse, oppressive suicidal thoughts, her survivor's guilt, the overwhelming death-duties, a posthumous life, her fear of learning something unexpected about her intimate companion after his death, and her sense of having a personal apocalypse.

Widows are the protagonists of "Pumpkin-Head," "Probate" and "Sourland." Children whose fathers are dying in hospital suffer abuses in "The Beating" and "The Barter." Children with broken, distant parents are cast adrift in "Bonobo Momma" and "Lost Daddy."

The protagonists are wounded, passive but highly observant protected women or children who share what Oates' calls the grieving person's inability to focus on, "the life of the more-than-personal, the greater-than-personal." This makes them vulnerable, easy victims. Instead of the nebulous grief and foggy fear of A Widow's Story, the stories offer tangible villains — spiders, snakes, and callous parents — and visible losses — amputations and deformities.

The stories also bring experimentation and playfulness of language into the experiences. Sentences weave "a nightmare of mangled and thwarted movement." They are fragmented and filled with charged verbs or halted passive voice. In "The Story of the Stabbing," words convey the jerking movements of traffic. In "Donor Organ," a suicidal, obsession with death comes in a rush of thought without a single period (it conveys the sense of the survivor left behind — an ending without an ending). In "Amputee," the word 'and' is always '&' in Jane Erdley's girlish abbreviated voice.

This playfulness and creativity breathes life and relief into the menaced experiences rendered in the cloistered, fearful perspective of Sourland: Stories' protagonists.

"If I have lost the meaning of my life, and the love of my life, I might still find small treasured things amid the spilled and pilfered trash," Oates writes in A Widow's Story.

In her stories, words become such redeeming treasure.

I had the opportunity to see Oates at Seattle Arts and Lectures at Benaroya Hall answering questions about A Widow's Story. While I appreciated seeing the famed writer, it felt tragic. Oates has adapted a survival strategy of separating her writer persona, JCO, from her self. However, it was hard not to see cruelty in isolating a person on stage for an academic discussion of grieving her husband's death.

Death and grief should be aired as part of our shared experience, but I wished this event had focused on Sourland: Stories instead.

Often people turn to non-fiction to challenge themselves and to learn. We read non-fiction with an intent to pull knowledge from a source, but fiction — stories — well provoke thought and contemplation within ourselves. Stories may be the best way to explore some topics, particularly those that offer no definite, forthright conclusion. Frequently, in the human experience, there is no one conclusion to arrive at, nor can there be one singular guru or guide — knowledge comes via journey and discovery and stories provide ways to enter into experience from a variety of perspectives with compassion and empathy.

A Widow's Story quotes:

"Harrowing to think that our identities — the selves people believe they recognize in us: our "personalities" — are a matter of oxygen, water and food and sleep — deprived of just one of these our physical beings begin to alter almost immediately — soon, to others we are no longer "ourselves" — and yet, who else are we?"

"Utterly naive, futile, uninformed — to think that our species is exceptional."

"When you sign on to be a wife, you are signing on to being a widow one day, possibly. When you sign on to be a writer you are signing on to any and all responses to your work."

"For the woman is likely to outlive the man — and to be the chronicler of his life/death. The woman is the elegist. The woman is the repository of memory."

Sourland: Stories quotes

"Is there a soul is a question I ask myself when I am alone, I am afraid of my thoughts when I am alone." — "Bounty Hunter"

"The life we live in our bodies, it's so strange isn't it? You don't ever think how you got in. But you come to think obsessively how you'll be getting out." — "The Barter"

"She felt a stab of love for him—a stab of terror—for in love there is terror, at such times." — "Sourland"

"How do such things happen you ask & the answer is Quickly!" — "Amputee"

Of note, Oates' references to science and science fiction:

Ray Bradbury's "There will Come Soft Rains"

H.G. Wells' "The Time Machine," the first of his Seven Scientific Romances

Asimov's Chronology of the World

Librarian Jane Erdley, the protagonist in the "The Amputee," meets her lover when he asks about James Tiptree

In A Widow's Story, the reader enters Oates' grieving — a harrowing, exhausting experience. When the reader puts the book aside — frequently — to take a break, to breathe it emphasizes the widow's plight — she has no ability to pause, no method of escape. Oates examines her personal grief intensely, but also comes to sees her state — one shared with other widows — as a kind of disease that must be lived through. Oates, who began writing her story as A Widow's Handbook, concludes that there is no profundity, no wisdom to be gained in grief, "...or, if there is...it's a wisdom one might do without." Instead, her advice boils down to a sentence, "...on the first anniversary of her husband's death the widow should think I kept myself alive."

Sourland: Stories contain many of the same ideas and images as Oates' memoir — hospitals as memory pools, the vulnerability of the surviving spouse, oppressive suicidal thoughts, her survivor's guilt, the overwhelming death-duties, a posthumous life, her fear of learning something unexpected about her intimate companion after his death, and her sense of having a personal apocalypse.

Widows are the protagonists of "Pumpkin-Head," "Probate" and "Sourland." Children whose fathers are dying in hospital suffer abuses in "The Beating" and "The Barter." Children with broken, distant parents are cast adrift in "Bonobo Momma" and "Lost Daddy."

The protagonists are wounded, passive but highly observant protected women or children who share what Oates' calls the grieving person's inability to focus on, "the life of the more-than-personal, the greater-than-personal." This makes them vulnerable, easy victims. Instead of the nebulous grief and foggy fear of A Widow's Story, the stories offer tangible villains — spiders, snakes, and callous parents — and visible losses — amputations and deformities.

The stories also bring experimentation and playfulness of language into the experiences. Sentences weave "a nightmare of mangled and thwarted movement." They are fragmented and filled with charged verbs or halted passive voice. In "The Story of the Stabbing," words convey the jerking movements of traffic. In "Donor Organ," a suicidal, obsession with death comes in a rush of thought without a single period (it conveys the sense of the survivor left behind — an ending without an ending). In "Amputee," the word 'and' is always '&' in Jane Erdley's girlish abbreviated voice.

This playfulness and creativity breathes life and relief into the menaced experiences rendered in the cloistered, fearful perspective of Sourland: Stories' protagonists.

"If I have lost the meaning of my life, and the love of my life, I might still find small treasured things amid the spilled and pilfered trash," Oates writes in A Widow's Story.

In her stories, words become such redeeming treasure.

I had the opportunity to see Oates at Seattle Arts and Lectures at Benaroya Hall answering questions about A Widow's Story. While I appreciated seeing the famed writer, it felt tragic. Oates has adapted a survival strategy of separating her writer persona, JCO, from her self. However, it was hard not to see cruelty in isolating a person on stage for an academic discussion of grieving her husband's death.

Death and grief should be aired as part of our shared experience, but I wished this event had focused on Sourland: Stories instead.

Often people turn to non-fiction to challenge themselves and to learn. We read non-fiction with an intent to pull knowledge from a source, but fiction — stories — well provoke thought and contemplation within ourselves. Stories may be the best way to explore some topics, particularly those that offer no definite, forthright conclusion. Frequently, in the human experience, there is no one conclusion to arrive at, nor can there be one singular guru or guide — knowledge comes via journey and discovery and stories provide ways to enter into experience from a variety of perspectives with compassion and empathy.

A Widow's Story quotes:

"Harrowing to think that our identities — the selves people believe they recognize in us: our "personalities" — are a matter of oxygen, water and food and sleep — deprived of just one of these our physical beings begin to alter almost immediately — soon, to others we are no longer "ourselves" — and yet, who else are we?"

"Utterly naive, futile, uninformed — to think that our species is exceptional."

"When you sign on to be a wife, you are signing on to being a widow one day, possibly. When you sign on to be a writer you are signing on to any and all responses to your work."

"For the woman is likely to outlive the man — and to be the chronicler of his life/death. The woman is the elegist. The woman is the repository of memory."

Sourland: Stories quotes

"Is there a soul is a question I ask myself when I am alone, I am afraid of my thoughts when I am alone." — "Bounty Hunter"

"The life we live in our bodies, it's so strange isn't it? You don't ever think how you got in. But you come to think obsessively how you'll be getting out." — "The Barter"

"She felt a stab of love for him—a stab of terror—for in love there is terror, at such times." — "Sourland"

"How do such things happen you ask & the answer is Quickly!" — "Amputee"

Of note, Oates' references to science and science fiction:

Ray Bradbury's "There will Come Soft Rains"

H.G. Wells' "The Time Machine," the first of his Seven Scientific Romances

Asimov's Chronology of the World

Librarian Jane Erdley, the protagonist in the "The Amputee," meets her lover when he asks about James Tiptree

I liked this much, much more than I liked Didion's work on the same subject. I thought this was a little more true, a little more real. As someone who has been very fortunate in life not to have dealt much with death and grief, I think this put a new perspective on how to handle other's grief without making a bigger mess of things.

This is what you hope for in a memoir of loss: realness. Oates delivers in a raw depiction of her loss and first year of widowhood. Neat mantras of hope or resilience are not to be expected, nor are they in here. Instead, this text is a dance with every wife's fear, and the worst part, that life goes on when that fear is realized.